Dead-end elimination

The dead-end elimination algorithm (DEE) is a method for minimizing a function over a discrete set of independent variables. The basic idea is to identify "dead ends", i.e., "bad" combinations of variables that cannot possibly yield the global minimum and to refrain from searching such combinations further. Hence, dead-end elimination is a mirror image of dynamic programming, in which "good" combinations are identified and explored further. Although the method itself is general, it has been developed and applied mainly to the problems of predicting and designing the structures of proteins. The original description and proof of the dead-end elimination theorem can be found in [1].

Contents |

Basic requirements

An effective DEE implementation requires four pieces of information:

- A well-defined finite set of discrete independent variables

- A precomputed numerical value (considered the "energy") associated with each element in the set of variables (and possibly with their pairs, triples, etc.)

- A criterion or criteria for determining when an element is a "dead end", that is, when it cannot possibly be a member of the solution set

- An objective function (considered the "energy function") to be minimized

Note that the criteria can easily be reversed to identify the maximum of a given function as well.

Applications to protein structure prediction

Dead-end elimination has been used effectively to predict the structure of side chains on a given protein backbone structure by minimizing an energy function  . The dihedral angle search space of the side chains is restricted to a discrete set of rotamers for each amino acid position in the protein (which is, obviously, of fixed length). The original DEE description included criteria for the elimination of single rotamers and of rotamer pairs, although this can be expanded.

. The dihedral angle search space of the side chains is restricted to a discrete set of rotamers for each amino acid position in the protein (which is, obviously, of fixed length). The original DEE description included criteria for the elimination of single rotamers and of rotamer pairs, although this can be expanded.

In the following discussion, let  be the length of the protein and let

be the length of the protein and let  represent the rotamer of the

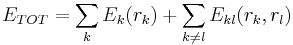

represent the rotamer of the  side chain. Since atoms in proteins are assumed to interact only by two-body potentials, the energy may be written

side chain. Since atoms in proteins are assumed to interact only by two-body potentials, the energy may be written

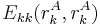

Where  represents the "self-energy" of a particular rotamer

represents the "self-energy" of a particular rotamer  , and

, and  represents the "pair energy" of the rotamers

represents the "pair energy" of the rotamers  .

.

Also note that  (that is, the pair energy between a rotamer and itself) is taken to be zero, and thus does not affect the summations. This notation simplifies the description of the pairs criterion below.

(that is, the pair energy between a rotamer and itself) is taken to be zero, and thus does not affect the summations. This notation simplifies the description of the pairs criterion below.

Singles elimination criterion

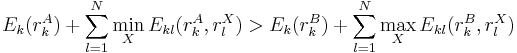

If a particular rotamer  of sidechain

of sidechain  cannot possibly give a better energy than another rotamer

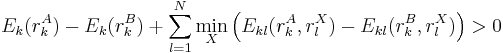

cannot possibly give a better energy than another rotamer  of the same sidechain, then rotamer A can be eliminated from further consideration, which reduces the search space. Mathematically, this condition is expressed by the inequality

of the same sidechain, then rotamer A can be eliminated from further consideration, which reduces the search space. Mathematically, this condition is expressed by the inequality

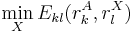

where  is the minimum (best) energy possible between rotamer

is the minimum (best) energy possible between rotamer  of sidechain

of sidechain  and any rotamer X of side chain

and any rotamer X of side chain  . Similarly,

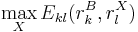

. Similarly,  is the maximum (worst) energy possible between rotamer

is the maximum (worst) energy possible between rotamer  of sidechain

of sidechain  and any rotamer X of side chain

and any rotamer X of side chain  .

.

Pairs elimination criterion

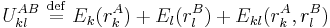

The pairs criterion is more difficult to describe and to implement, but it adds significant eliminating power. For brevity, we define the shorthand variable  that is the intrinsic energy of a pair of rotamers

that is the intrinsic energy of a pair of rotamers  and

and  at positions

at positions  and

and  , respectively

, respectively

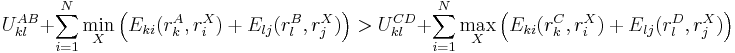

A given pair of rotamers  and

and  at positions

at positions  and

and  , respectively, cannot both be in the final solution (although one or the other may be) if there is another pair

, respectively, cannot both be in the final solution (although one or the other may be) if there is another pair  and

and  that always gives a better energy. Expressed mathematically,

that always gives a better energy. Expressed mathematically,

where  ,

,  and

and  .

.

Energy matrices

For large  , the matrices of precomputed energies can become costly to store. Let

, the matrices of precomputed energies can become costly to store. Let  be the number of amino acid positions, as above, and let

be the number of amino acid positions, as above, and let  be the number of rotamers at each position (this is usually, but not necessarily, constant over all positions). Each self-energy matrix for a given position requires

be the number of rotamers at each position (this is usually, but not necessarily, constant over all positions). Each self-energy matrix for a given position requires  entries, so the total number of self-energies to store is

entries, so the total number of self-energies to store is  . Each pair energy matrix between two positions

. Each pair energy matrix between two positions  and

and  , for

, for  discrete rotamers at each position, requires a

discrete rotamers at each position, requires a  matrix. This makes the total number of entries in an unreduced pair matrix

matrix. This makes the total number of entries in an unreduced pair matrix  . This can be trimmed somewhat, at the cost of additional complexity in implementation, because pair energies are symmetrical and the pair energy between a rotamer and itself is zero.

. This can be trimmed somewhat, at the cost of additional complexity in implementation, because pair energies are symmetrical and the pair energy between a rotamer and itself is zero.

Implementation and efficiency

The above two criteria are normally applied iteratively until convergence, defined as the point at which no more rotamers or pairs can be eliminated. Since this is normally a reduction in the sample space by many orders of magnitude, simple enumeration will suffice to determine the minimum within this pared-down set.

Given this model, it is clear that the DEE algorithm is guaranteed to find the optimal solution; that is, it is a global optimization process. The single-rotamer search scales quadratically in time with total number of rotamers. The pair search scales cubically and is the slowest part of the algorithm (aside from energy calculations). This is a dramatic improvement over the brute-force enumeration which scales as  .

.

A large-scale benchmark of DEE compared with alternative methods of protein structure prediction and design finds that DEE reliably converges to the optimal solution for protein lengths for which it runs in a reasonable amount of time[2]. It significantly outperforms the alternatives under consideration, which involved techniques derived from mean field theory, genetic algorithms, and the Monte Carlo method. However, the other algorithms are appreciably faster than DEE and thus can be applied to larger and more complex problems; their relative accuracy can be extrapolated from a comparison to the DEE solution within the scope of problems accessible to DEE.

Protein design

The preceding discussion implicitly assumed that the rotamers  are all different orientations of the same amino acid side chain. That is, the sequence of the protein was assumed to be fixed. It is also possible to allow multiple side chains to "compete" over a position

are all different orientations of the same amino acid side chain. That is, the sequence of the protein was assumed to be fixed. It is also possible to allow multiple side chains to "compete" over a position  by including both types of side chains in the set of rotamers for that position. This allows a novel sequence to be designed onto a given protein backbone. A short zinc finger protein fold has been redesigned this way[3]. However, this greatly increases the number of rotamers per position and still requires a fixed protein length.

by including both types of side chains in the set of rotamers for that position. This allows a novel sequence to be designed onto a given protein backbone. A short zinc finger protein fold has been redesigned this way[3]. However, this greatly increases the number of rotamers per position and still requires a fixed protein length.

Generalizations

More powerful and more general criteria have been introduced that improve both the efficiency and the eliminating power of the method for both prediction and design applications. One example is a refinement of the singles elimination criterion known as the Goldstein criterion[4], which arises from fairly straightforward algebraic manipulation before applying the minimization:

Thus rotamer  can be eliminated if any alternative rotamer from the set at

can be eliminated if any alternative rotamer from the set at  contributes less to the total energy than

contributes less to the total energy than  . This is an improvement over the original criterion, which requires comparison of the best possible (that is, the smallest) energy contribution from

. This is an improvement over the original criterion, which requires comparison of the best possible (that is, the smallest) energy contribution from  with the worst possible contribution from an alternative rotamer.

with the worst possible contribution from an alternative rotamer.

An extended discussion of elaborate DEE criteria and a benchmark of their relative performance can be found in [5].

References

- ^ Desmet J, de Maeyer M, Hazes B, Lasters I. (1992). The dead-end elimination theorem and its use in protein side-chain positioning. Nature, 356, 539-542.

- ^ Voigt CA, Gordon DB, Mayo SL. (2000). Trading accuracy for speed: A quantitative comparison of search algorithms in protein sequence design. J Mol Biol 299(3):789-803.

- ^ Dahiyat BI, Mayo SL. (1997). De novo protein design: fully automated sequence selection. Science 278(5335):82-7.

- ^ Goldstein RF. (1994). Efficient rotamer elimination applied to protein side-chains and related spin glasses. Biophys J 66(5):1335-40.

- ^ Pierce NA, Spriet JA, Desmet J, Mayo SL. (2000). Conformational splitting: a more powerful criterion for dead-end elimination. J Comput Chem 21: 999-1009.